Randal Pinkett strode into the salmon-coloured marble atrium of Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue, stepped into a lift that glided up to the 26th floor and entered an office that, along with a vista of wintry Manhattan, was lined with signed memorabilia and magazine covers bearing the face of Donald John Trump. The first and only African American winner of the reality TV show The Apprentice had arrived for his first day at work.

But when he walked in, Pinkett recalls, Trump was methodically working through a foot-high stack of magazines and newspapers on his desk. Each item in the stack had a Post-it note; and Trump took an item off the top of the stack, put it on his desk and opened it at the Post-it note. He read the relevant article then put it to the side. Disconcertingly, this ritual continued throughout their half-hour meeting in early 2006.

“So I’m wondering,” Pinkett says, “is this guy reading current trends in real estate, is he reading stock market coverage, is he reading about global business? I lean over as we’re talking and I realise everything he’s looking at is an article about himself. In fact at several points in the conversation Donald got so excited about what he was reading about himself that he would pick up the magazine and hold it up to me and say, ‘Look Randal, do you see that The Apprentice was number one in the ratings last week, isn’t that great?’

“Apparently somebody’s job responsibility is to find all this stuff and to organise it for him to read. I can only conclude that Donald loves reading about Donald.”

Donald loves reading about Donald. He has, according to many who know him, study him or write about him, made Donald his life’s work. Now he is seeking to perfect his masterpiece. His Jovian self-belief helped him sweep aside 16 rivals, including governors and senators, to become the first non-politician in decades to win a major party’s nomination for president. Barring a spectacular rebellion, the billionaire tycoon’s coronation will take place next week at the Republican convention in Cleveland ahead of what could be the ugliest election fight ever against Hillary Clinton.

How Donald Trump got to this once unthinkable, preposterous height is a story of immigrant ancestors working hard and making good, of hustling and hucksterism, of show business and showmanship, of success and celebrity, of bending the truth and branding the enemy, of a particular interpretation of “the pursuit of happiness”.

It is also a story of monumental ego undented by self-doubt. Trump’s swagger, eager to establish himself as the alpha male in the room, is said to be matched only by his lack of introspection. “He is a world-class narcissist,” says David Cay Johnston, author of the upcoming The Making of Donald Trump, who estimates his worth at no more than $1bn. “Donald believes that he is this incredibly great person and if you don’t recognise that, you’re a loser.”

Once, boasting of his golfing prowess, Trump asked journalists: “Do I hit it long? Is Trump strong?” It would be no great surprise if, should he become president, he ordered his face carved into Mount Rushmore alongside Washington, Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Lincoln.

But if there is one object that symbolises him, it is perhaps a mirror. Mirrors line the backdrop of the Trump Grill at Trump Tower, creating the illusion that it is double its actual size, while the lobby is full of shiny, reflective surfaces. Mirrors decorate the gaudy, gilded, Versailles-style ballrooms of Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s would-be winter White House in Florida. His former butler there, Anthony Senecal, 84, says: “He’s really got good taste in mirrors.”

But not, it seems, a rearview mirror. Mark Singer, who profiled Trump for the New Yorker in 1997, writes in a new book, Trump & Me:

“OK,” I say. “You’re basically alone. Your wife is still asleep” – he was then married, but not for much longer, to his second wife, Marla Maples – “you’re in the bathroom shaving and you see yourself in the mirror. What are you thinking?”

From Trump, a look of incomprehension.

Me: “I mean, are you looking at yourself and thinking, ‘Wow. I’m Donald Trump’?”

Trump remains puzzled.

Me: “OK, I guess I’m asking, do you consider yourself ideal company?”

(At the time, I deemed Trump’s reply unprintable. But that was then.)

Trump: “You really want to know what I consider ideal company?”

Me: “Yes.”

Trump: “A total piece of ass.”

Singer’s profile determined that Trump does not have an interior life. He “had aspired to and achieved the ultimate luxury”, it concluded, “an existence unmolested by the rumbling of a soul”.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Trump was probably best known to millions as the presenter of the American version of The Apprentice when, last June, he launched his wildly improbable presidential campaign at Trump Tower. After a now famous descent on an escalator, the property developer delivered a speech in which he said of Mexican immigrants: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

Poison was introduced to the American body politic. It contained two key ingredients of the Trump philosophy: the scapegoating of immigrants and what he describes as “truthful hyperbole” which, he claims, is an innocent form of exaggeration and very effective form of promotion. Or to put it another way, “truthiness”, as defined by TV satirist Stephen Colbert – truth that comes from the gut rather than facts. These two ingredients are, in fact, baked into the Trump family history, where they stretched the truth about their own immigrant story to improve their prospects.

His German grandfather, Friedrich Trump, was 16 when he arrived on a boat in lower Manhattan with a solitary suitcase in 1885. According to biographer Gwenda Blair, he learned English, became a naturalised US citizen, changed the spelling of his name to Frederick and made his way to Seattle to make his fortune – in the red-light district. He leased a tiny restaurant named the Poodle Dog, which had a kitchen and a bar and advertised “private rooms for ladies”.

Blair says: “I began to look at Trump’s father and got a little bit of a notion of his grandfather and thought, wow, this is really a dynasty. This whole three-generation century of capitalism: they so embody that. The immigrants, the nose for the market, the getting it, that’s what counts, the salesman, the incredible work ethic. They’re all real strivers, really hard workers. Never back down, never give way, always follow success.”

Frederick Trump moved the family to Queens, New York, opened an office and bought some properties, but was killed by the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918. The business was inherited by his 12-year-old son, Fred, who survived the Great Depression and, Blair writes, told a “flat-out lie” by pretending to be a prosperous estate agent executive. He began to build an empire as a property developer and by the late 1920s was selling houses in Queens for nearly $4,000 each. He walked construction sites after hours picking up nails and putting them back into barrels to be reused.

Fred claimed to be of Swedish, not German, descent because of anti-German sentiment in the US between the world wars. Until 1990, including in his 1987 best-seller, The Art of the Deal, Donald Trump himself claimed Swedish, not German, ancestry, even though his German grandmother lived across the street from the family until her death. It was an intergenerational white lie that arguably speaks volumes about Trump’s life and career of truthiness.

In 1936 Fred Trump married Mary MacLeod, herself an immigrant from Stornoway in the Outer Hebrides, once described by Donald Trump as “serious Scotland”. They settled in Jamaica Estates, a secluded suburb in Queens with Tudor revival houses and English street names such as Avon, Chelsea, Croydon, Henley, Kent and Somerset. The Trumps’ first, relatively modest, home was on Wareham Place and is currently up for sale. A Muslim family lives two doors away and the community is now middle class and cosmopolitan.

Joseph Charles, 66, a languages professor born in Haiti, says: “I love this neighbourhood. This is the United Nations here. I don’t see anyone on this block voting for Trump, to tell the truth. I don’t like what he stands for and what he’s been saying about different ethnic groups. He has an immigrant background like everyone else so I don’t understand where he’s coming from. After a black president, he must be the ‘great white hope’.”

The Trump family’s upward mobility is unmissable in their second abode, where Donald – born in June 1946 – and his four siblings spent most of their childhood, which is on a parallel street and an altogether grander affair with 23 rooms. Seventeen brick steps lead up a hill to the entrance, framed by a colonial-style portico, stained-glass crest and six white Doric columns. Neighbours dub it the “Gone with the Wind mansion”.

There wasn’t much point in people in the area trying to keep up with the Trumps. They had Cadillac Convertibles parked in the driveway, with licence plates FT and FT1, and a swimming pool, though not many books. Mark Golding, a close childhood friend of Trump from ages six to 13, recalls being driven there by the family chauffeur.

“It had a basement that had this great electric train set-up that I was really envious of Donny for having,” says Golding, 69, now a lawyer in Portland, Oregon. “There were four or five trains and they would go all around and pass each other, one would go up a bridge and down. It was the most amazing train set you’ve ever seen.”

Golding, the son of a physician, would sometimes sleep over at the Trump house and, on Saturday mornings, the boys watched children’s TV shows such as Andy’s Gang, and Rin Tin Tin. “I remember that he had a colour TV at a time before we even got our first TV. Colour TV at that time was really pretty awful but I remember thinking wow, that’s pretty amazing. They had a cook and a chauffeur and that was a bit more than we had, and my parents were not poor by any means.”

Trump was the tallest boy in school and Golding was second tallest, he recalls. “He was a good guy, at least to me. Some of the kids thought he was a little bit of a bully but I always got on pretty well with Donny. I don’t have specific memories of him ever bullying anybody else. At that time he was never a great student and actually didn’t get along all that well with most of the teachers.”

Trump’s father was somewhat formal and strict, a quiet conservative and friend and donor to Barry Goldwater’s doomed 1964 campaign for president. His mother was sophisticated and impeccably dressed. In The Art of the Deal, Trump remembered his mother “being enthralled by the pomp and circumstance” of watching Queen Elizabeth’s coronation on TV. “She always had a flair for the dramatic and grand,” he wrote. “She was a very traditional housewife, but she also had a sense of the world beyond her.”

On Sundays the family drove to Manhattan to worship at Marble Collegiate church, which would later host Trump’s wedding and his parents’ funerals. The head pastor was Norman Vincent Peale, dubbed “God’s salesman” and author of the tremendously influential bestseller The Power Of Positive Thinking.

Among its directives: “Formulate and stamp indelibly on your mind a mental picture of yourself as succeeding. Hold this picture tenaciously. Never permit it to fade. Your mind will seek to develop the picture … Do not build up obstacles in your imagination.”

Blair says: “I think that’s what Trump has done. Everything is a success. I think we’ve seen that over the last year and occasionally marvelled at it. Wow, this guy is good at that! He has harnessed a lot of things, like Twitter, to assist him in doing that. He was like that from the start but he’s good at figuring out how to adapt.”

Indeed, the influence of The Power Of Positive Thinking on Trump and his election campaign is not to be underestimated. He told the Iowa Family Leadership Summit last year: “I still remember [Peale’s] sermons. You could listen to him all day long. And when you left the church, you were disappointed it was over. He was the greatest guy.”

But abruptly, the 13-year-old was yanked out of this serene life and packed off to the New York Military Academy (NYMA), a private boarding school. Blair, who interviewed him extensively, explains: “The story he tells is that he and another kid snuck into Manhattan on the subway and got switchblades, evidently with nothing bad in mind but they seemed cool, and dad sent him off to military school. Off he went and apparently just loved it.”

Far from breaking him, military academy was the making of Trump. He thrived on the opportunity for competition over everything from tidying his room to shining his shoes and climbed the ranks. Cadets underwent basic military training (each was assigned an M1 rifle and learned how to break it down), studied an academic curriculum (Trump’s interest ended at geometry) and played sport (Trump excelled at baseball and basketball). Contemporaries recall that the academy had its share of bullying, including physical abuse, but that Trump was never involved as either perpetrator or victim.

The young cadets were living in the shadow of the cold war and endured the uncertainty of the Cuban missile crisis, then the assassination of President John F Kennedy in 1963. Peter Ticktin, 70, now a lawyer in Boca Raton, Florida, says: “It had a big effect on all of us. We were all in shock. Everyone cried” – including Trump.

Ticktin was a platoon sergeant while Trump, two years his senior, was a company captain. “He was self-confident, maybe a little smug. I wouldn’t go so far as to say arrogant because he was extremely approachable. There was no reason not to like Donald Trump. He was a good person and I think he still is. The same as he’s still tying his tie the same way [a Windsor knot], our honour code of not to lie, cheat or steal is still in him.

“I don’t think we had one guy out of 99 who would have had a bad word to say about Donald Trump.”

Another NYMA contemporary, Mike Pitkow, 67, a resident of Hilltown Township in Pennsylvania, adds: “There were many student officers who were quite egotistical and power hungry and Donald was not like that. I wouldn’t say he was modest but he had a sense of purpose: he seemed like he knew he was destined for something where he didn’t have to exude any power plays or ego or whatever. He was a decent and, I’d say, a nice guy.”

Trump went on to Fordham University, then the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with a degree in economics in 1968. He helped manage his father’s portfolio of residential housing projects for the middle class in Brooklyn and Queens and became favourite to succeed him after his elder brother, lacking the killer instinct that their father sought, became a pilot. His brother died at 43 due to alcoholism, a tragedy that Trump said led him to eschew alcohol, cigarettes and drugs all his life.

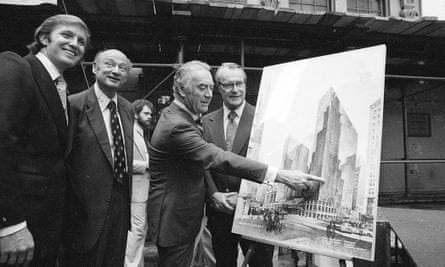

Trump made the most of his head start and, with a ferocious work ethic – he rises around 5am each day – set about building an empire. He crossed the East river to Manhattan, a much bigger and more lucrative stage, transforming the rundown Commodore Hotel into the Grand Hyatt and erecting the 68-story Trump Tower, where a portrait of Fred, who died in 1999, still overlooks a bar. Trump properties rose across America and around the world.

Paul Willen, an architect who worked with him on the Grand Hyatt project, remembers a rare occasion when Trump was forced to back down over his plan for a vast complex, including the world’s tallest building, at a disused railway yard on Manhattan’s upper west side. “As a practical matter, once he had made his decision to build our scheme instead of his, I can’t say he was an unreasonable client,” Willen says. “Turning around the way he did, I had a certain admiration for his ability to do it quickly, efficiently, without any fuss.”

Willen, 87, adds: “He was overbearing and very imperious and lording it over us but in the final analysis he would listen to us and he had to. He was building real buildings and he had to acknowledge us as architects and engineers and construction people and he was reasonable.”

Trump, who favours hand-sewn suits from Italian menswear specialist Brioni, carved out a reputation as an audacious deal maker and master marketer. In his world, everything was the biggest, best and most beautiful because everything he touched would turn to gold.

Trump also opened hotels and casinos, a venture that led to four bankruptcy filings, though he has never declared personal bankruptcy. The slump in his fortunes at the end of the greed-is-good 1980s coincided with the collapse of his marriage to Ivana, his wife of 14 years, following an affair with former beauty queen Maples.

Trump was forced to sell buildings, a Boeing 727 and his yacht, the Trump Princess, not that he was ever much of a sailor. But even at this personal and professional nadir, it seems, his self-belief was unshaken. Roger Stone, 63, a political consultant and friend since meeting Trump in 1979, claims: “I don’t think he ever lost faith in himself because he is the greatest negotiator that ever lived and, at a certain juncture, he figured out that he was worth more to the banks alive than he was dead, so if they took him down, they were going down with him and therefore he was able to negotiate incredible deals which not only saved his company but allowed him to rebuild from scratch.

“When it comes to negotiation, he has got ice water in his veins … He’s a very tough negotiator. He leaves nothing on the table. I would not have wanted to be the banks because even though he owed them money, he had them by the throat.”

Trump’s recovery in the 1990s – inevitably the cue for another book, The Art of the Comeback – included forays into the entertainment business and he took ownership of the Miss Universe, Miss USA and Miss Teen USA beauty pageants. But it was in 2003 that Trump’s celebrity gained liftoff with The Apprentice, in which contestants competed for a shot at a management job within his organisation. He claimed in a financial disclosure form that he was paid a total of $213m by NBC.

For years the equation of Trump = success was pumped into millions of homes. Blair notes: “It gave him 10 years of being in front of the American public being the boss, being CEO, hiring people, famously firing people, being the guy who can fix it, the one who knows everything, being the big authoritarian patriarchal guy. I think that has imprinted on a lot of people, that they ‘trust’ him, that that makes him ‘trustworthy’. That combined with the reality TV phenomenon in which it became acceptable to have something that wasn’t really true. It legitimised a kind of a not-quite-true thing and shifted our idea of what’s an acceptable version of reality.”

Pinkett, 45, who won The Apprentice in 2005, agrees. “Reality TV, among other factors, has created this hyper-celebrity culture in America that we’re all now immersed in,” he says. “Celebrity has become its own form of capital and Donald is one of the chief beneficiaries of that cultural phenomenon of celebrity translating into capital. He went from a successful entrepreneur to a media personality and he is now cashing in on that celebrity capital.”

Now chairman and chief executive of a management, technology and policy consulting firm, Pinkett, from Somerset, New Jersey, continues: “I believe Donald is a very insecure man. Only somebody who is insecure, given Donald’s accomplishments and success and fame and wealth, feels the need to fire back harder than people fire at him and do it in a derogatory, demeaning way.

“About two years ago somebody accused Donald of being a racist and Donald’s response to the racism claim was, ‘I hired Randal Pinkett as my apprentice and he has done an outstanding job, so how could I be a racist?’ Two months ago, when I held a press conference stating that I don’t think Donald is fit to be president, Donald’s response is: ‘Randal’s a failure and he did a terrible job for me.’ That’s classic Donald.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Trump Tower, located beside 178-year-old luxury jewelry store Tiffany & Co, throbs with activity in midtown Manhattan. On a recent weekday families in T-shirts and shorts milled around the Trump Bar, Trump Grill – where the menu includes Trump Scotch, a selection from the Trump Winery, a Trump Tower steak sandwich and Trump’s homemade ice cream – Trump Cafe, Trump’s Ice Cream Parlor and Trump Store, which sells his books, “Make America great again” baseball caps, “Success by Trump” deodorant sticks, “Donald J Trump signature collection” ties, Trump National Golf Club baseball caps and Trump Tower jelly beans and sour beans.

The goods are posh but unpretentious, American but not artis

anal, a world away from Brooklyn’s hipsters. A recent photo showed Trump on his private jet eating a McDonald’s Big Mac,fries and Diet Coke. Supporters say this shows his authenticity. Stone, who has wanted him

to run for the White House since 1988, recalls the Republican national convention that year. “He was invited to a private black-tie dinner with then Vice-President George H W Bush and his running mate then Senator Dan Quayle. He looked at the engraved invitation which had been delivered by hand to his hotel suite and he said to me, ‘Call down to the desk and find out who has the best cheeseburger in town. Let’s stick this and go out for a burger.’

Trump could not be accused of being an elitist, highbrow, patrician snob. Unlike Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry and Bernie Sanders, he has not been spotted at the hit Broadway musical Hamilton. His desert island discs would, friends say, probably include Paul Anka, Tony Bennett and Elton John. Favourite movies include Pulp Fiction, Zulu and Sunset Boulevard, in which ageing actress Norma Desmond declares with Trumpian conviction: “I am big! It’s the pictures that got small.”

In his New Yorker profile, Singer writes of Trump’s viewing habits during a flight to Mar-a-Lago. “He’d brought along Michael, a recent release, but 20 minutes after popping it into the VCR he got bored and switched to an old favorite, a Jean Claude Van Damme slugfest called Bloodsport, which he pronounced ‘an incredible, fantastic movie’.

“By assigning to his son the task of fast-forwarding through all the plot exposition – Trump’s goal being ‘to get this two-hour movie down to 45 minutes’ – he eliminated any lulls between the nose hammering, kidney tenderizing, and shin whacking. When a beefy bad guy who was about to squish a normal-sized good guy received a crippling blow to the scrotum, I laughed. ‘Admit it, you’re laughing!’ Trump shouted. ‘You want to write that Donald Trump was loving this ridiculous Jean Claude Van Damme movie, but are you willing to put in there that you were loving it, too?’

In the nine years since, Singer has seen nothing to alter his view of Trump as unburdened by a hinterland. “People talk about a private Trump and a public Trump,” he says in his Manhattan apartment. “I’m not so convinced because I’ve seen both and the bombast is there, the obvious extreme self-involvement has always been there. He doesn’t have a sense of irony. He’s a terrible listener but that’s a characteristic of narcissistic people. They’re not engaged with anybody else’s issues.”

Singer’s New Yorker colleague writer Ken Auletta, 74, tells a character-defining story. Auletta, whose father was a nodding acquaintance of Trump’s father at a restaurant where each often had lunch, bumped into Trump years later at a New York Knicks basketball game. “He came over to me and he said, ‘Hey, Kenny!’ I don’t know anyone who calls me Kenny. He says, ‘Hey Kenny, how’s your pop?’ I said, ‘Well, actually he died.’ ‘Oh, I’m sorry to hear that.’

“So the next year at a Knicks game I see him and he says, ‘Kenny, how’s your pop?’ So I said, ‘Well, actually he died.’ ‘Oh, I’m sorry to hear that.’ The third year I see him, he says, ‘Hey Kenny, how’s your pop?’ I glared at him and I paused for a second and then I said, ‘My dad’s the same,’ and I walked away.”

Trump himself is a father and grandfather. He divorced Maples in 1999 and married Melania Knauss, a Slovenian model, in 2005. He has five children from three marriages. The offspring from his first – Donald Jr, Ivanka and Eric – now help run the Trump Organisation and are playing an ever-expanding role in the election campaign. Stone, speaking from Miami Beach says: “I don’t think anybody would deny that he has a healthy ego but what he’s really into is his family. He’s extraordinarily proud of his family and proud of the role they’re taking in the business.”

Stone, who has given many speeches on Trump’s behalf, agrees there is little room for self-reflection. “I don’t think he has a lot of time for psychobabble. Like Nixon and Reagan, both of whom I worked for, he’s not terribly introspective. He’s more interested in the next fight, the next battle.”

The Trump persona appears to have devoured the man who created it. But does the great big beautiful winner, aiming to become the oldest US president in history, not shiver just a little when he contemplates death? “No,” replies Senecal, who butlered for him for nearly three decades. “He figures he’s going to live forever.” Pause. “And he probably will.”